Smishing and Flubot require solutions, MNOs advise against opening links, and shoot themselves in the wallet

What do Flubot and SMS phishing have in common? Shocking daily headlines, the Wild West of URLs, and one easy solution to stop both in their tracks.

If you have heard anything about the newest Flubot attack, you have probably also warned your parents and others not to trust or click any link from an SMS message. This is bad news for MNOs. Fraud has been on a steep incline since the COVID-19 pandemic began, and consumers, while under attack from the virus, are also under attack electronically and financially.

Smishing, malware, and the Flubot are dominating headlines. These attacks may seem like separate threats, but they have a lot in common: They both begin with an SMS message and end in devastating financial losses to subscribers. Mobile operators have responded by issuing warnings to consumers, yet they are missing an enormous opportunity to save the day and savour the glory (and press coverage) any hero should.

Anatomy of the Flubot attacks

We will describe the most common Flubot attacks currently seen, however the companies, industries, and other details about the content and technique of the attack are sure to evolve and spread. Although this is currently accurate, it can be considered an example of a Flubot attack, as many possibilities and variations exist.

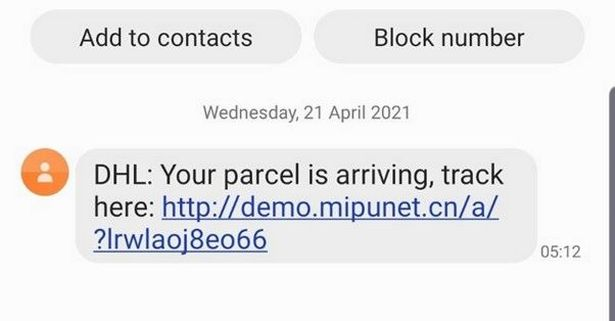

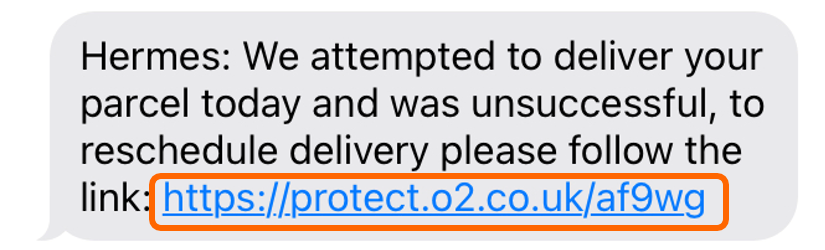

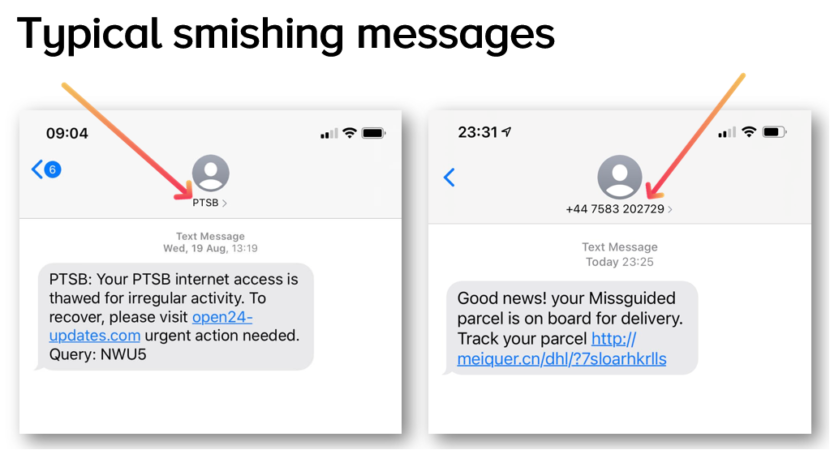

An attacker sends an SMS with a claim about an undelivered package, or a problem with a bank account. They also frequently utilise SMS spoofing (falsifying the sender party ID) to make the message appear more credible. This means that the message will appear in the same thread as previous messages from a legitimate sender. Frequently these messages are sent in high volumes (spam) but this is not always the case.

The message, purporting to be from a bank, delivery service, or other trusted entity includes a link to their website to resolve the problem. This link may lead to a website domain that was only purchased the same day, or even a legitimate domain with some kind of corrupted page, or user hosted content section (such as github). The page is styled to look like the DHL or bank website and convincingly prompts the user to download a fake look-alike app (such as the DHL tracking app). However, this is not any normal app; it is an APK file, which is a kind of 3rd party app, not vetted by the Google Play store. It could contain just about anything.

The instructions ask you to change some settings in your phone to allow external apps, but this does not specifically require the user to change their “security” settings. If you follow the instructions (as many do) and download the app, you will get much more than you bargained for, The app is a trojan for malware, that is now able to access sensitive data including your banking details, etc, by overlays to sit above website browser windows, recording keystrokes, collecting typed data and credentials.

To add insult to injury, the Flubot may also access your contact book and send SMS text messages to anyone and everyone in your directory in order to propagate itself. Imagine your phone taking a big infected sneeze all over your friends and family.

The attackers now have enough of your private data and credentials to empty your bank account, steal your identity, and destroy your life as you know it. You can get the malware off your phone, but the damage is done.

Proofpoint suggests that Flubot has spread to the UK, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, and Spain. The Flubot has already collected 25% of Spanish mobile numbers, affected over 60k devices, sent millions of messages, is present on “all networks” according to Vodafone and shows no signs of slowing.

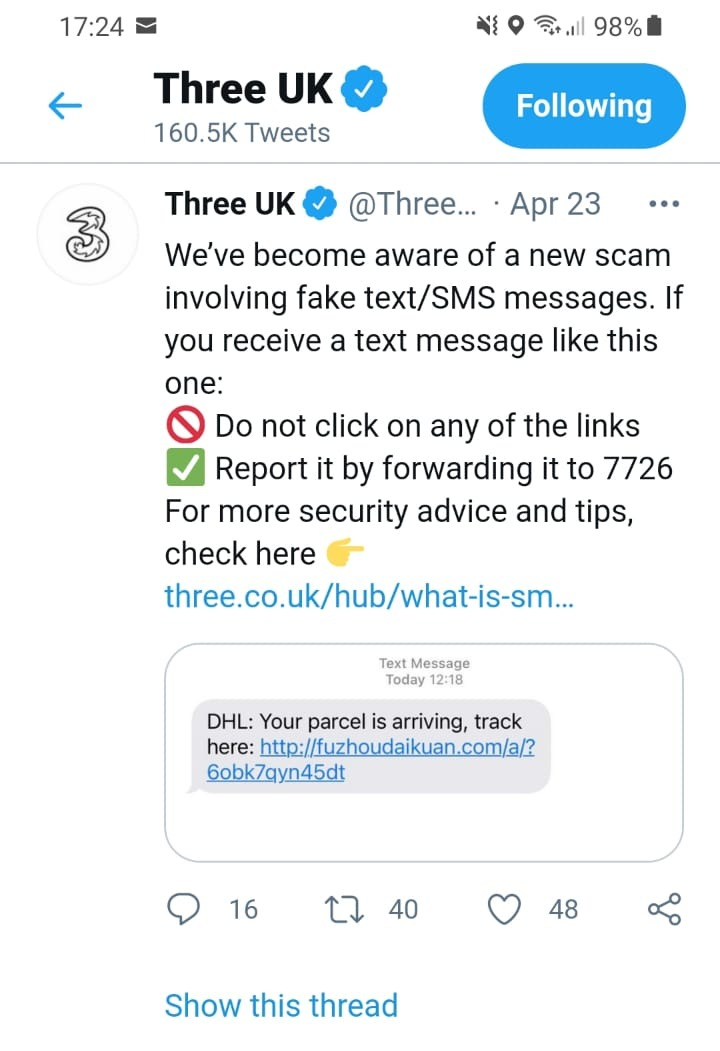

Operators have responded by issuing statements warning the public of the new scam, and less publicly suggesting that the responsibility for this epidemic lies with Google and the Android operating system for allowing a workaround to download unapproved apps in the first place. The speed and complexity of this attack make it a tough knot to untangle, and as of yet no operators have offered a solution.

Anatomy of a smishing attack

Smishing techniques vary and often incorporate other touch points, such as calling the victim impersonating a trusted entity and using social engineering to trick the victim into giving away sensitive information. We will describe the most basic and common smishing technique, however there are many variations to this attack.

An attacker sends an SMS message with information about a missed delivery, COVID vaccination, fraud warning from a bank, or other compelling message. The message contains a call to action and a URL to follow. The link usually leads to a very recently created, elaborate, and convincing look-alike page for the entity the message claimed to be from. This website will then ask for an inordinate amount of personal information, such as your credit card information, and date of birth.

After “voluntarily” sharing this information with the attackers, they are able to drain your accounts and wreak havoc on your identity. Often banks are powerless to stop them and unwilling to accept liability for any fraudulent activity with origins outside their institution and technological reach. In their eyes, the consumer has committed gross negligence, “freely given” their credentials, and the bank is not responsible for the loss.

According to Proofpoint, there are 6 smishing attacks per second targeting just 10 US and UK banks. Every week sees a new scam reported, a new entity targeted, and a new victim losing their life savings or small fortune to elaborate smishing scams. The response from mobile operators in the wake of smishing attacks that have increased substantially (328% in the last year) is to again, issue warnings with tips to look out for, and sometimes the sweeping advice again not to follow any link in any SMS.

What’s the Difference?

Smishing affects Android and Iphone users alike, for one. Even iPhone users who may be immune to Flubot are just as susceptible to smishing scams.Smishing does not compromise the phone in any way, and works solely by funneling the user to the phishing website. The Flubot on the other hand, is smishing plus a trojan malware bonus. The malware is more sophisticated and able to gather more information over time.

Another key difference is that the Flubot is self-propagating and represents a real threat to mobile network stability and quality of service. Having the ability to send unlimited SMS messages from each infected handset, makes Flubot an added liability for network operators. Unchecked increase in message volumes could create outages and disrupt service.

What they have in common

SMS as an attack vector: They both start with a malicious URL delivered via SMS, phish sensitive data, and end with innocent people losing their shirts.

Highly lucrative and well-funded

Both attacks result in huge gains for the attacker. Even with a low percentage of successful attacks overall, the net gains can be enormous. We must keep in mind that in many cases, hackers are not shady characters in a basement, but rather highly sophisticated businesses such as professional ransomware firms who legitimately employ professionals to design and perpetrate such attacks. Their business model is defrauding the unsuspecting at the highest scale and efficiency possible.

What is the problem for the operator?

News and Accountability

The most immediate concern is the current news cycle. The old adage that there is no such thing as bad press does not hold true when it comes to grandma losing her life savings to fraud. When fraud or security breaches are exposed on a single network, we know that all operators are likely at risk of a similar fate.

We can predict that the illusion of protecting subscribers through warnings and tweets will not last. Android remains an easy scapegoat only because of its juxtaposition to the iPhone, which has no such loophole. As long as all networks allow this problem to continue, network insecurity is seen not as a loophole, but just the status quo. The public might wonder if SMS, by nature, can even be secured by the operator. It will, however, only take one network publicly and visibly ending this problem for subscribers to demand more from their own mobile networks.

DoS and A2P

Flubot carries the added threat of denial of service if it is able to send SMS messages unchecked by users, handsets, and the network itself. Proofpoint estimates malicious SMS messages to be in the tens of thousands per hour in the UK alone. This is no small concern, yet the threat we should all be concerned about – as an industry – is the slow and steady destruction of SMS and A2P as a revenue stream.

Precaution is also catching. As we have seen in the response to the COVID pandemic, where precaution abounds, so do economic impacts, and for mobile networks, the economy in question is their own. As people exercise greater caution with SMS messages, networks stand to lose untold millions if not billions in lost SMS traffic, and especially lucrative A2P traffic. A2P messaging is a $43 billion business. When we see networks actively and desperately warning their customers to distrust SMS, they are, to an extent, sealing their own fate.

As more and more operators release official statements warning subscribers not to click on any “suspicious” link in any “suspicious SMS”, the more SMS becomes synonymous with “untrusted”. The average person quickly recognises the limits of their expertise in fraud detection which results in people choosing not to open any SMS or clicking on any link from an SMS — to be on the safe side. SMS itself falls under a veil of suspicion, which has repercussions on lucrative A2P SMS volumes. It is difficult to imagine DHL and other companies who have been targeted and imitated ever again expecting their customers to trust an SMS from them, and that is only the tip of the iceberg.

Challenges to securing URLs in SMS

Many solutions are proposed to this problem, but frankly, none of them are working well enough. Malicious URLs are still responsible for over 90% of all cyberattacks. Each solution addresses part of the problem, and while none are in-effective in what they aim to do (like hand-washing, mask-wearing, and social distancing), these measures slow the problem but are far from a real cure.

Spam filters and SMS firewalls

An SMS firewall is an excellent tool in combating all these attacks. Spam filters and SMS firewalls are built to identify and block various types of SMS fraud such as spam and number spoofing, which contribute to the volume and efficacy of an attack, however an SMS Firewall alone cannot verify the security of any website URL contained in the message without an external query.

Even the best SMS firewalls will not catch all malicious SMS message, especially those sent at low volumes, or with fresh tricks to get around current content filtering policies. A few will always sneak through, and the real threat is not in the message, but the URL itself. A firewall is only as good as its ruleset, so firewalls that are not continually updated or effectively maintained in the face of emerging threats are no solution at all.

Blocklists

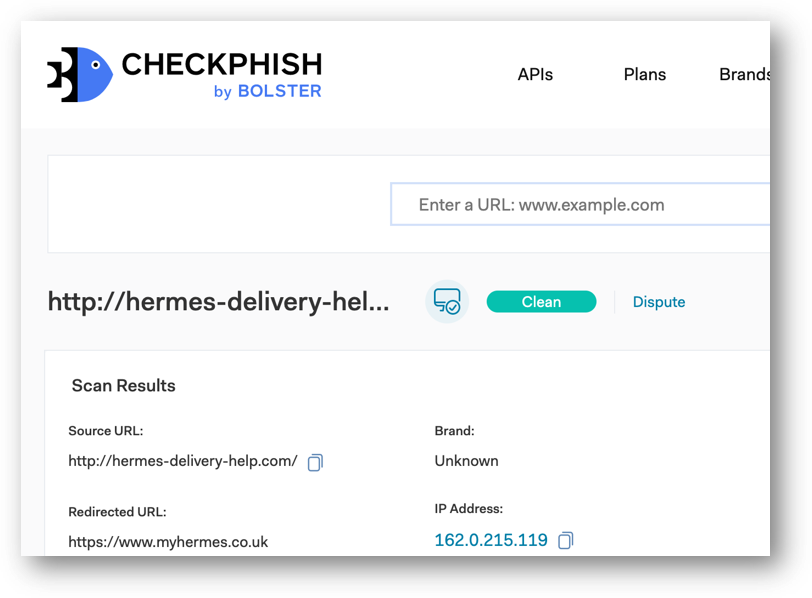

Blocking access to known fraudulent websites seems like a very common-sense approach to protect subscribers, and of course, should be done – however when we look into what it takes for a malicious URL to get to that blocklist, we see this is far from a solution. The first thing it takes to get to that blocklist is time itself.

According to Google, criminals only need their deceptive URL to be up and running for 7 minutes before achieving their goal in a targeted attack on a person or company, and 13 hours for a bulk campaign. In practice, all security vendors take 2-3 days average to investigate and block new dangerous domains.

It is estimated that a new phishing site is set up every 20 seconds, and attacks happen quickly. Most smishing attacks use cheap website domains that were registered the same day or within days of the attack itself. This does not allow enough time to verify if a site is safe or dangerous, because nearly a million new domains are registered every single day.

Secondly, these blocklists rely largely on reports of fraud by consumers rather than a proactive screening. That is to say, someone must discover how fraudulent the site is the hard way before it can be flagged as such. Even after reporting a suspicious domain, it may be many more days before action is taken. In this span of time, much damage can be done and blocking the website will be far too late for many.

Web domains are not always what they seem. In the Flubot attack, we are seeing attackers use well-known and trusted domains such as google.play.com or github, which would not be found on a blocklist, however the malware is actually hosted and served from the user content section of these websites. This user content is never qualified by the domain owner or anyone else, so the unique URL may itself be malicious, even if the domain is credible and resistant to being blocklisted.

SSL or TLS

SSL (also known as TLS) certificates are a joke. Some SSL certificates can be self-certified in less than a day. The mere presence of “an SSL certificate” is inconsequential, and is in fact, as good as not having one at all. The existence of this certificate does nothing to protect the consumer in this circumstance. They may be more effective on a desktop than a mobile device but in all cases cannot be considered an effective form of either protection or information.

To a consumer, as long as a website has any kind of SSL certificate, they will not receive a warning, and therefore believe they are protected. The problem is that there are different levels of scrutiny for different kinds of SSL certificates. An e-commerce site (which asks for shipping and payment details), and a home decoration blog should not use the same kind of SSL certificate, and yet if they do, the subscriber is none the wiser. Fraudsters can get a DV SSL certificate for their smishing website easily. “The process only requires website owners to prove domain ownership by responding to an email or phone call.”

Education and publicity

Public outreach relies on mobile phone users casually hearing about new threats through news, social media, and other outlets. Operators might even warn subscribers more aggressively through email campaigns or even an SMS campaign. These approaches are scattergun and will not ultimately reach everyone they need to. Proofpoint also found that 72% of adults are not familiar with smishing.

Although operators must take action to warn their subscribers of impending threats, they may be hesitant to draw attention to fraud and security concerns of this sort. Afterall, when the public is taught not to trust links in SMS, that is precisely what they will do. In fact, they begin to distrust SMS overall.

Verified Senders

Google, Mobile Ecostytem ForumEF and others have organised verified sender schemes in which only the brand registered to a sender ID is able to use that sender ID and all other attempts are blocked by the operator. This is a great solution for likely targets such as banks, in that someone cannot spoof and impersonate your bank and land messages in the same thread as your real bank. Unfortunately though, this approach only works if there are no grey routes, SIMboxes, or fraudulent channels into the network, which bypass this verification mechanism.

Thanks to the convoluted nature of how A2P SMS works though, we are all conditioned to receiving real genuine communication from long codes (phone numbers instead of alphanumeric IDs), so many of us would not even bat an eye at receiving bank communication from a strange long code number. Verified sender schemes are a worthwhile and commendable pursuit, but still do not come close to really solving the threat posed by smishing.

Other solutions:

Google includes a mechanism in the SMS feature, to ask customers if the website might be “spam” or not. Reliance on the general public is not accurate, also takes time, and whether it is “spam” or not… the phishing URL remains a problem.

Of course, we have to discuss the merits of AI and machine learning to automatically detect new dangerous domains and new dangerous URLs that are on safe domains. These technologies are great for many reasons, but they need time to learn, and even then it is mathematically impossible to get it right most of the time, let alone all of the time. Attackers only need to get it right once.

Is there a cure?

Arguably, yes. Let’s think in terms of a vaccine, and a treatment. Verifying the integrity of every single URL in every single SMS sent to subscribers is the fastest way to stop both Flubot and smishing in their tracks. For users and networks already affected by malware, there is a way to test and identify infected handsets, and thereby alert subscribers to the infection and help them to purge the malware from their device.

The vaccine – SMS Anti-Phishing

The ounce of prevention worth a pound of cure: Assume every URL is dangerous unless authenticated as safe. A URL verification approach to all URLs delivered through SMS messages is enough to stop smishing and malware from infiltrating your network and wreaking havoc on your subscriber base. None of the security solutions we’ve discussed get the solution wrong – however none are complete or robust enough to truly protect subscribers from these attacks. SMS Anti-Phishing ensures that every URL sent to every subscriber is safe and secure.

Imagine a world where there are no victims that fall prey to a phishing site in the several days before the site is reported as fraudulent and shut down. Malicious links are blocked and potentially dangerous links that have not yet been classified are delivered with a strong warning. Consumer education is an important component to protect against phishing, however the reach of tweets and press releases are not enough. Mobile operators are in a unique position to inform their subscribers about the veracity of every single link, directly to their phone, exactly when they receive it – and be the hero of this story.

Imagine that while subscribers in competing networks are bombarded with messages not to trust links in SMS messages — no matter the sender — your subscribers are informed with every single URL they receive, which links are safe to open, and which links have been blocked for their security. Communicating real security messages to the subscriber on a daily basis, deepens the trust the subscriber has in the network, by reinforcing the network’s ability and commitment to the customer’s safety. This, in turn, restores their faith in SMS messages in general, which results in higher open rates and higher conversion rates of A2P messages.

The Test and the Treatment – Malware detection

Obviously, the priority to stop this devastating e-plague is to stop the malicious links that lead to fraudulent websites in the first place, however if Flubot is already suspected on a network, steps to control and contain the damage must also be considered. Malware is usually invisible to the consumer, meaning that users who are now in the process of being victimised, may also be completely unaware of it. More than 1 in 100 mobile devices is infected with active malware even without the Flubot epidemic going around. This is another unique opportunity for mobile networks to save the day for their customers.

Using powerful broadband analytics and deep packet inspection, all devices on the network can be scanned for malware, viruses, and trojans without the need for downloading apps or any other interaction at the subscriber or device level. As an immediate remedy to the Flubot outbreak, the operator can issue a warning to infected subscribers with instructions about how to remove such malware from their device. Alternatively this can be an extra or optional security service the user subscribes to.

Malware and virus detection can also be used as a way to determine the extent of the impact, and detect and stop new attacks before they are able to run amok.

Achieving herd immunity to smishing and Flubot

Ultimately, these attacks will only fail where mobile network operators succeed.

The opportunity for networks to succeed here spans from operations to marketing and there is no reason that operators shouldn’t flex. As mobile data becomes more of a commodity, it is more and more difficult to add value to mobile plans and really stand out to customers. Security and protection that is visible to the end customer is a chance to escape the race to the bottom and give network branding a real advantage over competing networks.

Customer experience is not the only place security adds value. A2P is an incredibly lucrative revenue stream for many networks, especially those with robust A2P monetisation strategies and effective SMS firewalls. Should subscribers lose trust in SMS (and they are), this will lead to a devastating decrease in investment from legitimate enterprise who use A2P SMS as a marketing channel and delivery mechanism for one time passwords, two factor authentication and other messaging. As an industry we must fight to maintain SMS as a trusted channel for business.

The reasons to take real action on solving smishing and Flubot are clear:

- Subscribers will love you for saving them where giants like Google have failed

- SMS is a lucrative channel worth protecting

- It is the right thing to do

As an industry, it is up to us to make these attacks less successful. The more networks who step up to secure messaging, verify URLs, and protect consumers, the less attractive it is for attackers to target subscribers through SMS. This herd immunity is achieved when enough operators commit to ending these attacks on their network, and the time is now.

More information on the Cellusys SMS Anti-Phishing Solution

How SMS Anti-Phishing works

The SMS Anti-Phishing Solution can be used in conjunction with an SMS firewall or as a standalone solution for SMS phishing and Flubot attacks.

Every SMS is checked for the presence of a URL. Cellusys authenticates every URL against the Phishing Threat Intelligence Database registry. Even if the URL redirects multiple times across multiple domains, the destination URL will be authenticated:

The subscriber receives the message in one of three ways:

- Verified Safe URLs: Subscriber can open the link

- Potentially Dangerous URLs that cannot be verified: the link is replaced with a redirect link to a warning page explaining why the page is blocked, and urging the subscriber only to open with extreme caution.

- Dangerous URLs that are known: the link is replaced with a redirect link to a warning page explaining why the page has been blocked.

More Information about Fraud Insight solution for Malware

Sources:

https://therecord.media/massive-flubot-botnet-infects-60000-android-smartphones/

https://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/uk-news/o2-issue-urgent-scam-warning-20467000

https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-reference/smishing

https://www.juniperresearch.com/press/operator-a2p-messaging-revenues-62-billion-2023

https://www.thejournal.ie/bank-of-ireland-text-scam-2-5169511-Aug2020/

https://www.wandera.com/mobile-threat-landscape/

https://www.liquidweb.com/blog/ssl-certificates/-of-ssl-certificate

https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/guidance/flubot-guidance-for-text-message-scam

https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-56859091

https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/guidance/Flubot-guidance-for-text-message-scam

Tags: Flubot, flubot solution, malware, smishing, trojan, zero trustCategorised in: Blog